It should be clear to those who have paid attention to his career that Joe Wright is a boom-bust filmmaker. Sure, it’s alright to admit that you were initially fooled by the one-two punch of Pride and Prejudice and Atonement, which are as essential pieces of British aughts cinema as much as any Danny Boyle or Stephen Frears film (and perhaps even more so to a specific kind of bookish kid who grew up in that era), but it began to become clear after his dreadful ’09 effort The Soloist gave way to Hanna and Anna Karenina, one an excellent (and nearly unparalleled) action thriller, and the other a formally fascinating adaptation of an oft-adapted text. Then Pan came along, and you know how that went. He followed that disaster with a decent episode of Black Mirror, and the Winston Churchill biopic Darkest Hour, which saw him return to the era that initially made him a superstar director. So, if the pattern were to hold, it would suggest that his latest film, the mass-market paperback adaptation The Woman in the Window, must be an outright catastrophe. It certainly already has that reputation, with the Fox-Disney merger and then the COVID-19 pandemic delaying its release by a year and a half before it was finally offloaded to Netflix, all the while following rumors that the film was re-cut by Disney executives after it flopped with test audiences.

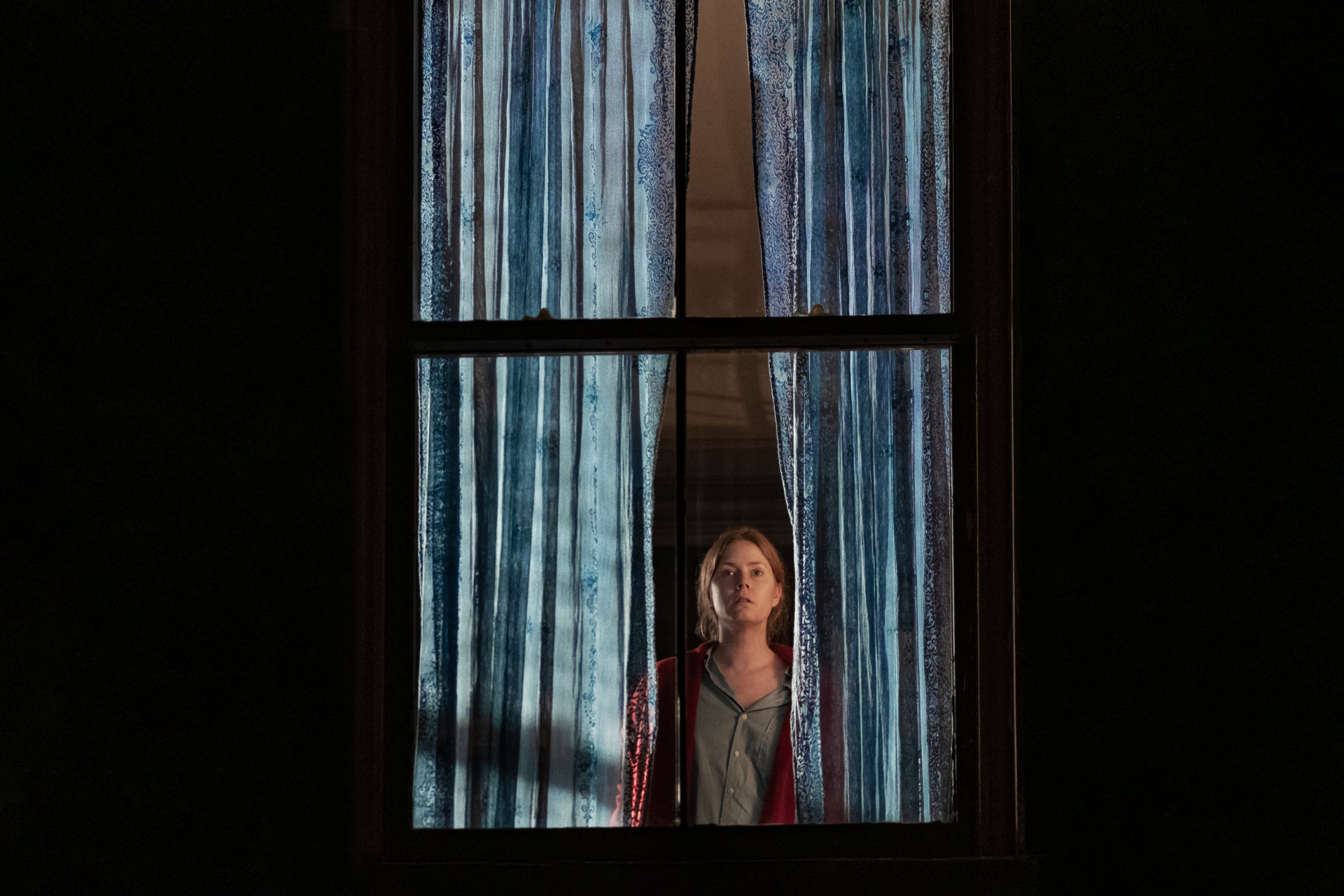

Rules, however, are meant to be broken. While it’s hard to put The Woman in the Window next to the capital-G Good films in Wright’s oeuvre, it certainly isn’t one of the bad ones, and it offers an interesting proof of that old Kurosawa quote about good films requiring good directors and good writers: It turns out, in fact, you can make a decent film if you only have a decent director. Nearly all the faults in this thriller stem from either A.J. Finn’s original novel or Tracy Letts’ adaptation of it for the screen, which takes a fun Hitchcockian premise and applies aspects of the gothic chamber drama to it. Our protagonist is Anna (Amy Adams), an agoraphobic child psychiatrist who spends her days holed up inside her massive West Side brownstone, gazing out into the street from her windows. She’s estranged from her loving husband (Anthony Mackie) and daughter, and her therapist (Letts) encourages her to keep taking her meds and to stay away from the booze. She listens to him only about the former, spending her nights in a wine-drenched stupor watching old movies, haunted by aspects of her past. But when a new family, the Russells, move in across the street, Anna begins to involve herself in their lives.

Well, to be perfectly clear, they intrude upon hers first. The family’s sensitive teenage son, Ethan (a swell Fred Hechinger), brings over a gift and finds himself opening up to the woman, given that she’s, you know, trained to comfort troubled adolescents. Make no mistake, Ethan is troubled: His overbearing father (Gary Oldman) is stressed and angry all the time, and is wrecking havoc on the young man’s psyche. This is further confirmed when Anna meets the boy’s mother, Jane (Julianne Moore), by pure happenstance during a stressful Halloween night, and the two seem to hit it off as friends, somewhat. The next night, from her window, Anna watches the woman get murdered by who she assumes is the husband (get it? The Woman in the Window goes two ways!). After she calls the police and two detectives (Bryan Tyree Henry and Janine Serralles) interview her and her slacker tenant (Wyatt Russell, looking and sounding more like his dad every day), she discovers, with a shock, that there’s another woman in the Russell house calling herself Jane (Jennifer Jason Leigh), saying that she — and only she — is the boy’s mother, and she’s never met this woman before. Of course, shit gets strange, and it’s pretty fun goings, in that pulpy airplane novel way.

As you’d expect from a Joe Wright film with this stacked of a cast, the performers acquit themselves well, though for whatever reason I couldn’t connect as much as I’d like to with Adams’ character. Perhaps it’s the way that these stories force us into constantly questioning the lead’s state of mind, even though in this particular type of thriller, we know better than to do that, and I wonder if the earlier moments in Letts’ script should have emphasized her humanity more rather than showcasing her estrangement from the rest of the world. Highlighting her trauma-and-booze-induced suffering at the start does make for a cheap reveal later on at a key moment in the back half of the film, but Letts, maybe obeying the structure of the novel, downplays what should be a dramatic moment soon after that reveal, perhaps contorted his characters a little too far in accommodating the author’s twists. It might be the pacing, though: We’re really immersed in Adams’ brownstone-centric universe early on, with new characters ambling their way into the periphery often by sheer narrative contrivance. Happily, Wright’s there to pick up many of the pieces for both writers, stringing together some of the more puzzling or vacuous choices with an emotional intelligence embedded specifically within the visuals.

Initially, Wright leans hard on the classical Hollywood influences that are supposedly embedded in Finn’s text, though it does come close to citing its antecedents in an overtly precocious way by having Adams’ character sit and watch, say, a psychoanalysis scene from Hitchcock’s Spellbound at an early point in the film — you’re barely twenty minutes in, and you’re already being reminded that you could be watching something better. But as he gets further and further away from the intrigue-free first third of the film, the director begins to ease more of himself back into the material, and what follows is a surprisingly colorful and smartly-constructed, if generic, thriller. I genuinely wish I could have seen this in a decent theater, because there’s a lot of lovely detail in Bruno Delbonnel’s rich cinematography, and if you’re going to limit yourself by holding fast to a single setting, well, you might as well draw it as beautifully as you can. In his capable hands, the color temperatures of otherwise bland rooms in Adams’ townhouse oscillate from blood reds to rainy blues to warm oranges to the white-blue-grey fuzz of television static, and he’s more than up to the task of helping to realize the surrealist touches in Wright’s imagery. There are echoes of Shutter Island in certain scenes, and the wild finale somehow finds itself at the intersection of Fulci and Wan, being a giallo-styled nightmare with the high shutter-speed physicality of modern horror.

So, yes, The Woman in the Window has its issues, but I’m honestly stunned that I had as good of a time with it as I did, given everything that was stacked against in the press and by my own biases. The last major release of this type, The Girl on the Train, was a film I truly loathed, so it was nice to be pleasantly surprised by something, and it should be especially vindicating for Wright, given how long it’s taken him to have this film seen. I have an odd feeling that this might actually be a bigger success than Netflix thinks it’s going to be, given that they seem to have undersold that they have a movie with legitimate star wattage hitting their service on Friday, because when one presses play, they’re really not going to get what they’ve expected from a lot of the streamer’s “original” content. It feels like a movie, after all, and that matters more than one might think.