There’s a blessing and a curse that comes with being in the first all-women band to score a Number 1 album on the Billboard charts. The blessing is that you’re a living part of history and glass-ceiling-shattering; the curse is that the feat becomes what you’re known best for, forever. Enter the plight of The Go-Go’s, whose debut record Beauty and the Beat kicked down barriers for women in music everywhere.

Now, almost 40 years later, bassist and Go-Go’s member Kathy Valentine is pushing for visibility again with her memoir and accompanying soundtrack All I Ever Wanted. This time, though, she’s opening new avenues specifically for women instrumentalists like her.

In the archives of music history, there are many gaping holes still being filled in decades later — holes where the stories of non-white, women, and non-binary musicians have been glossed over. Valentine’s book arrives as an essential piece of painting the true, complete picture of rock’s history, demonstrating what it means to be a woman in a band when you’re not the singer.

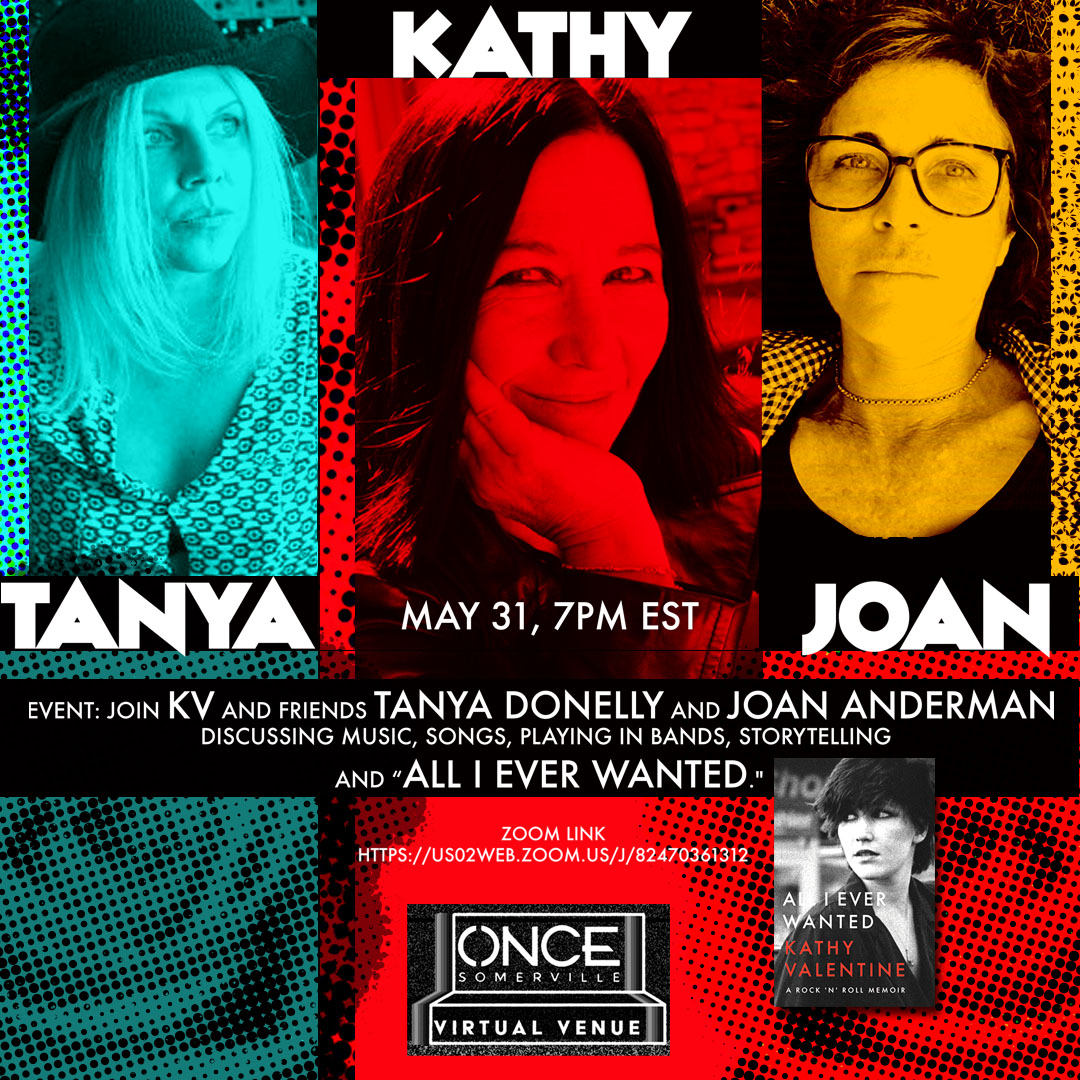

Ahead of her book event at ONCE Somerville’s “virtual venue” with Tanya Donelly and Joan Anderman this Sunday (May 31), Vanyaland hopped on the phone with Valentine to talk about the art of memoir writing, visibility for women in music, and honoring rock’s early icons that are all too often overlooked.

Victoria Wasylak: How are you coping right now with everything that’s going on? I feel like I’m rude if I don’t check in with people.

Kathy Valentine: Well, I’m doing fine. I’m a homebody anyways. I mean, I miss performing live, I should say that. And I don’t want to paint too rosy of a picture, I lost an immense amount of income. The Go-Go’s were going to be on tour this summer. I was going to do my very first book tour, which we’ll get more into that conversation, but it was the first time I was going out just being Kathy Valentine, not being a member of a band.

So having said all that, losing the income, losing the book tour, losing the speaking engagements – [the good news is] I’m not sick, yay! No one I know got sick. And I like working in my studio,I like making music. I’ve had to be really busy and active and keep on top of feeding this social media beast and trying to just not annoy people, but at the same time keep trying to sell my book, because how am I going to sell books?

I’m very glad that you’re at ONCE Somerville virtually at least. I know Tanya Donelly is also joining you for the Boston stop. How did that come to be?

Well, we’ve never met in person, but on social media we’ve been friends and following each other. I like the idea of appearing with other women musicians. I just tried to think of different [creatives] specific to that city. I knew Tanya was a local and I thought she likes the band — she was inspired a lot by The Go-Go’s. She’s so smart and just seemed like the right person to do this with. We also have John Anderman who, I thought would be great. I didn’t even know about her music career! I’ve only done these with two people, I haven’t done a three person one before but I like that it adds another element and dynamic.

Talking about your book, one of the things I think is so essential about it is that there are thousands of rock memoirs written by men, and there are many written by women singers or front people, but there are not many done by women instrumentalists. I guess you don’t really realize it until you stop and think about it.

Yeah, or they don’t talk about the music a lot [in their books]. That was a conscious thing. I really identify as a musician, I really do. I feel like I’ve been a working musician in a band non-stop for 45 years.

Well, you have.

Yeah, and if I’m not in The Go-Go’s, I’m in another band. There was no way I could write this without writing about how music was such a part of my life, even before I was a musician. This [music] is important, this has to be part of the narrative, to just start opening that door to normalizing the fact that women are just as valid and important in the musical landscape as men are. One way to start normalizing that idea is to make music part of the dialogue. In The Go-Go’s, never were we asked about the songwriting process, or our instruments, the practicing, how we picked up that instrument. We were doing massive amounts of interviews and nobody ever asked us about that.

It’s changed a lot, I’m not going to say it hasn’t. It’s changed a lot. But I’m glad you noticed that because I did consciously want to make sure that music was the thread in the book, even though it’s a very personable story, and you don’t have to be a musician and you don’t have to be a Go-Go’s fan to relate to it and have the story resonate.

We’ve come a long way since 1980, but also women who are the drummer, the bass player, the guitarist who isn’t the lead singer, a lot of times they don’t get a voice; they’re used in stories as “the hot bass player” or “that’s the band with the girl drummer,” and they don’t even get the dignity of having their name shared.

Yeah, I’ve heard people equate The Go-Go’s with Bananarama and the Spice Girls. And there’s nothing wrong with either of those musical acts, but how can you not make the distinction between a band and people that sing? I’ve had my mind blown more times than I care to tell you when that happens. And it’s not that I’m insulted —

It’s inaccurate.

Yeah, it’s like, did the Stones get confused within NSYNC, for God’s sake?

How do you feel about the progress or the lack of progress that’s happened since the start of The Go-Go’s? Between then and now with regards to how women instrumentalists are treated?

Well, I see a big change, and I see fantastic women musicians. You see it on major tours, with major artists. You never go, “Oh my God, P!nk’s got a female playing bass” or “Beyoncé has an all-female band.” Instrumentally and as players, I think that’s really changed. Hopefully an artist isn’t going, “hey, we need to be cool. We need to get a female in the band” or whatever. But somebody — a woman — is getting a job. That’s all I care about. And getting a job playing music. That’s a huge improvement but on other levels, I don’t see a lot of bands [of all women]. I’m not sure why that is. I think it’s probably has a lot to do with how difficult it is unless you’re making a lot of money. How do you have it all? How do you be in a band?

A guy can be 25, get married, become a dad, and still go out on the road. How does a woman do that, if she’s not at the stature where she can have her own bus and a nanny and all that stuff? If you’re not Heart or Chrissie Hynde? Even me, I took my baby on the road, and I brought a nanny. I didn’t make any money. So I think part of it is that. That the guys still get to go out and play music and have it all.

And again, something that I never really thought about until I was reading the book is that now it is very, very common for women to be in bands, but it’s still really uncommon to see a band without a cisgender man in it. It’s just strange, right?

It’s just sad because my longing back then was to just see more women in the culturally important landscape of rock music. That was what I wanted to do. When I saw Suzi Quatro, I didn’t just go, “I’m going to go home and be in a band” — I wanted to go home and be in a band with girls, with teenage girls my age. I said “we can do that.”

One particular part of the book that really struck me emotionally is when you reached out to your father, saying you were really serious about pursuing a music career. And he said, “That’s not a career of substance and that’s not something that women do.” Fortunately, you showed him wrong, and he came around and he admitted that. Do you think of this book as a contradiction to what he said, and to everyone who’s ever felt that way — that songwriting and musicianship isn’t a “woman thing”?

Yeah. I think so. For a lot of people, the first question they ask me is, “Why did you write the book?” I think that was a big reason. I think this is a story that should be told and I would like to think if it gets an audience and gets read enough that it would inspire other young girls to do that. And it’s a stupid thing to compare it to, but I just think of all the young women that go off to college and join sororities. I just think, what is that? That’s wanting to belong, that’s wanting a sisterhood, that’s wanting to be a part of something, and it’s so much like what I wanted. I wanted a sisterhood. I wanted to belong, I wanted to be a part of something. Part of me just thinks, “why aren’t more of them starting bands? You could get that same thing.”

***

It’s a visibility thing. You’re making your story available and visible to other young women, so that they can follow that. Because if it’s not there, it might not even register to them that it’s an option.

That’s true. And that’s one of the things that I think is so sad for what happened in the ’70s. During the ’60s and the ’70s, of the music and the bands that became culturally big touchdowns, whether it was David Bowie, or Led Zeppelin, or the Beatles… women are so absent from that landscape. If we had known and seen more women doing it — and they were! They just weren’t real successful or they didn’t have hits, but they were doing it and I had no idea. Suzi Quatro at age 14 was touring. She quit high school and was touring in 1964.

You can go on YouTube and you can find all these garage female bands that were playing in the ’60s. There was Fanny, who I’d never heard of. Fanny was in the early ‘70s before I saw Suzi Quatro. Goldie and the Gingerbreads, 1962. I’m three years old, and there’s an all-female band out on the road, playing with major guys. We didn’t have the internet, we didn’t have fanzines. There was no real way for a teenage girl in 1974 to know about all that if the band wasn’t huge. It’s a sad thing because I think there would have been a lot more girl [bands], like in England, in the wake of Suzi Quatro. I went there in ’77, and I was like, “what? There’s so many girls my age that play instruments.” They had Suzi Quatro that they grew up with. I just feel like if there’d been some access or some visibility that had happened before, I think more girls [would have been playing music then].

I’m grateful that the men that I looked up to, and the guys that I knew, that they supported me and didn’t laugh at me or dismiss me. Even these bands in the ’60s, guys were taking these [women] bands on the road. The Quatro Sisters told me they never felt looked down upon by the guys musicians. So that’s a super cool thing. But it’s just that adage that history is written by the victors.

I think there’s a lot of fascinating stories out there to be told. I feel like for women in music, it’s our history even if it wasn’t Top 40 or Top 10, or number ones, or giant album sales, or this and that. I still feel like it’s our history and that it’s valid. I’m still finding women that were trailblazers.

All rock memoirs have elements of darkness in them, but I was really surprised to see how deep you were able to dig in this book, talking about things like getting an abortion, or that night when everyone was blacked out on drugs and then you saw the tape [of your actions] the next day. Why did you choose to include that?

Well, because my number one goal in writing the book was writing a very good book, because I want to do this more. I’m a very practical person. I don’t mean this in a self-deprecating way, but, who gives a fuck that the bass player wrote a book? I knew it had to be really well-written, it had to be compelling, and it had to be very, very human. Because otherwise, who cares? And also, that would open the door to writing another book.

I wrote about it because it matters. If I am not going to write about what matters, I don’t see any point in writing a memoir. For me, a memoir that is done well means that you don’t flinch, you don’t look away, you don’t whitewash, you don’t sugarcoat. Part of my story is pain and deep sadness, and part of my story is remorse. I wanted to tell my story. I wasn’t telling The Go-Go’s story. I wasn’t writing the history of The Go-Go’s. I was writing my story from that slice, and how I changed, and how I started out, where I came from. I didn’t think anybody would understand how meaningful and profound making it in a band was to me, unless they knew where I’d come from. And I didn’t think anybody would understand how devastating and lost and confused I was at losing that band unless they knew where I came from. I didn’t want to write the social media equivalency of books, where everything is great and I’ve smoothed all the edges out of my life. That’s not what a memoir is for.

Prior to writing this book, did you feel like you were in a box? Everyone seeing you as “just a Go-Go,” and you had no identity outside of being a member of The Go-Go’s?

I felt like that when I got out of the band, when the band broke up, and I was very lost. When we got back in 1990 when I was sober, I knew that I would never let myself be defined by another person or a band or a job ever again. It was too painful to lose my sense of identity. But in the years since, with 30 years of sobriety, I have such a full life. I’ve educated myself and I’m a mom. I’ve done some great music — it’s not famous like the Go-Go’s, but I know that I’m really good. And at my age, I don’t need to be relevant. It’s not like I need to be heard, I just need to say it. It’s important to me to do that. But yes, the answer to your question is I felt like that was all I was known for — playing bass in the band that had their hits in the early ’80s.

It’s been something that I’m so proud of, and feel so blessed, and it’s opened so many doors. And, again, if I hadn’t been in The Go-Go’s… that’s the hook to make somebody want to read my book. But I think when you read the book, you’re going to go, “fuck, this is somebody that’s a lot more than someone that played bass on ‘We Got The Beat.’ This is a human being that really strived.”

I’m really excited at 61. I think it’s a really strong message in and of itself to be 61 saying, “Hey, I’ve been very safe. I’ve been playing it very safe, I’ve been the cool chick in the cool band for decades and decades.” And it’s safe. I have never had to take that risk of just putting myself out there. And then I did it [with the book]! I never wanted to be the star or in the spotlight. But when you write a memoir like I’ve written, then I can’t hide in the band anymore. It’s exhilarating. At this age to be pushing myself, it feels like the time to do it. Because if I don’t do it now, when would I?

It’s a whole different pushing yourself because this [writing a book] is its own art form. With The Go-Go’s, I think that’s a different form of pushing yourself. There’s pressure on a band that has only women in it — if you, as a band, had screwed up, then everyone would have written off women bands forever.

Well, that’s why we had such a hard time getting a record deal. They were not secretive about it, they would say flat-out, “There’s never been a successful all-female band. We can see the band’s popular, we can see that they can sell out the Whiskey A Go Go, but there’s never been a successful one, pass.” So yeah, you’re absolutely right. Thank goodness for our success. And it doesn’t need to be heralded over and over. There’s just as many girls starting bands now because they saw Avril Lavigne — I mean, there’s more! But there is a chain, there is a ripple effect. Absolutely.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

KATHY VALENTINE ‘ALL I EVER WANTED’ BOOK TOUR:: Sunday, May 31 at ONCE Somerville’s virtual venue:: 7 p.m., 18+, free :: ONCE event info