Note: The following interview discusses sexual assault and violence in the context of the new Netflix program ‘Unbelievable’, and may be upsetting to some readers. It also contains spoilers for the series.

For the past four years, the troubling story of Marie Adler has been in and out of the public eye, her tale circulating the media as a chilling true crime anomaly.

First, there was the article “An Unbelievable Story of Rape,” published in December 2015 on propublica.org. Then came the episode of This American Life, titled “Anatomy of a Doubt,” in February 2016. But nothing has re-created the story of Adler — and the other women affected in this largely Colorado-based case — in such a visceral way as the new Netflix series Unbelievable.

Released last Friday (September 13), the eight-episode drama maps out the sickening but true tracks followed by two Colorado detectives (played by Toni Collette and Merritt Wever), temporarily united while investigating suspiciously similar rape cases. The deeper the two women dig, the more their cases become inextricably bound — and to Marie’s (Kaitlyn Dever) story as well.

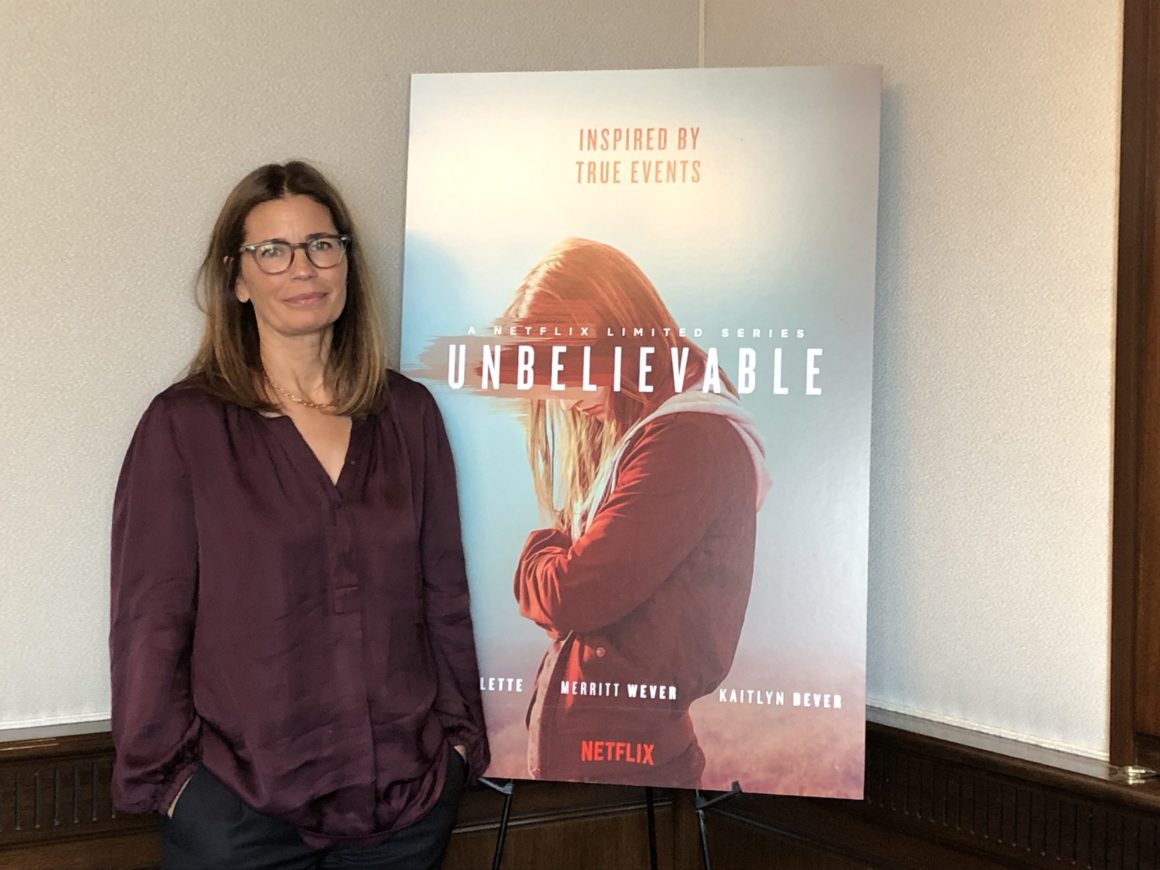

Program co-writer and co-director Susannah Grant spells out the complete narrative with an especially pristine form of clarity and honesty. Delicate when it counts, and brazen when it counts even more, Grant’s Unbelievable presents an unflinching account of justice, faithful to every woman involved. Grant sat down with Vanyaland last week to discuss the miniseries, sharing her own methods of researching the case, her thoughts on balancing facts with privacy, and how sexual assault isn’t a gendered issue.

Victoria Wasylak: How did you hear about this story/article to begin with?

Susannah Grant: I don’t remember if I just stumbled upon it in my own reading or if someone showed it to me, but I read it when it came out and immediately thought this would make for a great dramatic version of it, a narrative dramatization. For a moment I thought maybe it would be a good two-hour movie and then I realized there was so much in it, it would be better as a limited series.

That’s interesting, because in general it’s not a super “feel good” story because it’s a very difficult topic.

It’s about tough stuff, for sure. I mean, I’m really inspired by the detectives that Merritt [Wever] and Toni [Collette] play. I find every move they make in their investigation, really inspiring and forward-moving. I find it satisfying. But that’s maybe just me.

I’m surprised that you saw this and immediately felt, “I want to tell people about this.” Because it is a very, very difficult subject and very difficult story, with a lot of gut-wrenching moments in it. How did you translate that onto a screen and do it right? Because this isn’t made-up, you have to do justice by these [real] people.

A lot of the cues from that came from the article actually, because they did the same thing of balancing the really difficult things that Marie is going through and that get increasingly oppressive and kind of crippling as the show goes on. They balanced that with the progress and teamwork and forward movement of those women [detectives] in Colorado. So I feel like it was something in that balance that felt like it could hold this difficult issue in a way that would really hold the viewer. You know? I mean, it held me in reading it, and I’m not a deeply dark person. I’m a realistic person and I want to have the real conversations. But I didn’t really worry about that too much. I just thought this is a great story, just on the narrative level. It is a really engaging story, and yeah, it’s about difficult things, but it feels like the world is ready to talk about some difficult things.

Right. I had a similar experience watching it. You cringe a little bit, but I kept going back and wanting to see what happens next. You’re right, it works much better in an episode format than it would a movie. Also that’d be really hard to swallow in a whole sitting.

Yeah. And there are things that we’re able to do because we have eight hours that we never could do in a two-hour movie. The fact of how we can go through that investigation with Marie and really appreciate what that is for people, and why people say that the investigation sometimes feels like a second assault.

And at the same time go through the detective’s work, and realize that it’s not a straight line. There are dead ends you run into. You get to a point where you have no idea what information is going to mean anything, and what’s worthless, and what’s the nugget that’s going to get you to where you want to be. All of that would have to be streamlined in a movie. The wonderful thing about this moment in limited series that we’re having now is that we can have these stories that take more time.

And then you end up getting to spend more time with the characters and they become more complex and they end up being real people living through this. Which doesn’t mean you can’t have real people in two-hour movies, of course you can. But there’s a luxury in having eight hours to show a lot of sides of a character.

One thing I noticed is the way you laid the story out, and the casting and the dialogue, it really showed how differently all the different women [victims] were treated, like [how detectives treated] Marie versus Amber. Because everyone’s experience is different, but everyone deserves to have a comforting experience in recovery. And I thought that was really interesting that you, I would assume, took the care to show that.

Yeah. I mean, to be honest, we took some dramatic license with the women who had gone through that, who were survivors of this guy, because we just really wanted to respect their privacy. And so we tried to represent what was the truth of their experience, while changing a lot of the identifying facts about them.

But to understand that not every victim is going to react the same way. They’re as many different ways to react to trauma as there are humans on the planet. And the first person who doubts her [Marie] is a survivor of sexual assault herself, her foster mother who thinks, “Well, she’s not reacting like I did. So, I’m not sure if I believe her.” You know? And I think that’s a big misconception a lot of people have.

Did you do any additional research beyond the article when you were putting this together?

I did, yeah. We did a lot of research. Well, the real Bible of it was their book, Ken [Armstrong] and T. [Christian Miller]’s book, and the This American Life podcast, which was especially helpful to our actors, and the initial article. But they also gave us a lot of their research materials. They had police pull reports and all that and that was very helpful. But there were other things I looked at. There’s a pair of documentaries by Amy Ziering and Kirby Dick called The Hunting Ground and The Invisible War. Those were really helpful, just for me, getting a broader sense of the people who’ve been looking at this issue in depth longer than I have. Those were helpful. And then we did a lot of statistical research.

We had a researcher on staff with us in the room while we were figuring out [the story], and he was this wizard, who could answer any question we had within 15 minutes and produce all sorts of data for us.

How long did that extra layer of research take?

Well, we probably spent about three weeks planning out that the arc of the eight episodes. I had already written the first two episodes by the time we got in there. But then getting into the real investigation, the meat of the investigation, we spent about three weeks planning out the next six episodes together. People went off and wrote their separate scripts. Three weeks in there, I think, three, maybe four.

***

Adding onto what you had said earlier, what were the liberties that you had to take when you were doing this?

There were ones we took with the characters, really out of respect for people’s privacy. We tried to stay very close to the facts, and the work that those detectives do in the series is the work that those two detectives did in Colorado. But we changed their names. We held onto a couple of identifying characteristics, just ones that felt like they were relevant to who they were as investigators and people. When it comes to their inner lives, and their personal lives, and the way they talk, and the way they interact, and that relationship, we took a lot of creative license there.

I mean, these are detectives. They didn’t sign up to be characters in a miniseries that was going to be broadcast all over the world. So, they were fine with us fictionalizing them. I think they probably preferred it. I also think there were some life rights issue given that the work they had done was for the state and so they couldn’t sign that away. And then there were character consolidations.

There were three men who were really helpful on their team. They’re consolidated into that one character, the FBI guy who works with them. And then the data, the computer guy who’s also there. Those are consolidations of multiple characters. You’re fictionalizing, consolidating, you can’t fit everyone into a narrative like this or it just ends up looking jumbled. But we really tried to stay really faithful to the truth of the experience while changing some of the details.

Right. I’m just marveling at that because, again, it sounds very daunting. It’s the balance aspect. I feel like if you do anything wrong, it could tip the scale in either direction – if it’s not true enough, or maybe it’s too real for the people who were involved.

Well the too real was …I mean, we were really careful about that and not just us as filmmakers, but CBS, the studio, was also really adamant that we protect these people’s privacy, and that we change their identifying characteristics enough. Everybody was on board with that. And in terms of the tonal balance, I think that’s just kind of an inner ear balance sense that you have as a storyteller.

How do you think this is going to be received in the Me Too era of the past couple of years, where people have been a lot more open about their experiences of being assaulted?

I hope it finds a good audience. We started it before the Me Too movement hit. I mean, it was definitely received with the same energy that led to the Me Too movement. But no, it seems to be hitting at a time when people are really welcoming this conversation. I mean, I hope they find it. I hope it finds a good place in that conversation.

Right. And I think you would’ve done this even if that hadn’t happened.

Oh yeah. We were all set and Netflix was fully committed. They put their full weight behind it well before Me Too and Time’s Up.

What do you want people to take away from the series?

We really just hope that it’ll engage people, and people who are already part of the conversation, it’ll keep them in it. And the people who maybe have felt like they’re outside of this conversation, if it can pull them in and say, “No, no, no, this is worth your attention. Pay attention to it.” That’s great. And it’s really not a male/female issue.

There’s this report that came out in the last few days about the numbers of sexual assaults on men in the military. It’s 10,000 a year. So this is not a women’s issue, sexual assault. I mean, there are men who have suffered it and in a lot more silence than women have. It’s really not a women’s/men’s issue. It’s a perpetrator and victim issue. And it’s really not a gendered issue. It doesn’t have to be a gendered issue at all.

I wanted to talk a little bit about the dialogue in the series, because again, with the way that you showed how the different women were treated, I thought a lot of the dialogue was really deliberate. There were some notes that I wrote down that really stood out to me and how you addressed common misconceptions or common attitudes. One was that “there’s status in being a victim.”

Yes. That line was written by Ayelet Waldman and Michael Chabon. That’s the script they wrote, yes. That was good. It was a very good knowing scene. Yeah.

There’s one exchange when a gentleman comes in [to the police station] because he thinks his friend is being suspicious, and he says that his friend, “forces women to have sex with him.” And then she [the detective] repeats it back to him. “Oh, so your friend rapes people.” And he’s like, “No, that’s not what I said.” She says, “No, actually, that is exactly what you said.” And I just thought, again, it was very deliberate. They’re teaching moments.

I mean, you really can’t write something with the intention of teaching, but what you can do is park yourself in an area where miscommunication happens, and you’ll probably find some really interesting interpersonal dynamic there. If you find the stress points with an issue, and those are two really good stress points. I’m glad you noticed those.

Maybe not teaching points, but talking points.

Right.

That definitely stood out to me. How do you do that without being preach-y?

Well, you do it by having real characters say it and have it be genuinely motivated in the moment. That’s a lovely scene written about a nervous guy who feels like he should do the right thing, but doesn’t want this to be as big a deal as he fears it might be. And you’re in there with him, trying to make it a little bit less bad than he thinks it might be. And so when he says it from that place, you’re with him as a character, and you understand him emotionally. And I think that takes some of the lesson out of it, because it’s coming from an authentic place in the moment.

‘Unbelievable’ is available to stream now on Netflix.